TruffleHog now detects JWTs signed with public-key cryptography and verifies them for liveness. This new detector has already found hundreds of live JWTs for our customers.

We recently deployed a new JSON Web Token (JWT) detector across all TruffleHog platforms, including TruffleHog Enterprise. The immediate impact has been substantial: it found hundreds of live JWTs for our customers within hours of deployment. This performance has positioned it among our top 25 detectors.

Although a JWT cannot in general be verified for liveness, it can be when it is signed using public-key cryptography and we can retrieve the public key. TruffleHog’s new JWT detector takes this approach, maintaining its standard of providing liveness verification for every exposed secret it reports.

This post covers some of the technical details behind the new JWT detector.

Refresher: JWTs are stateless auth technology

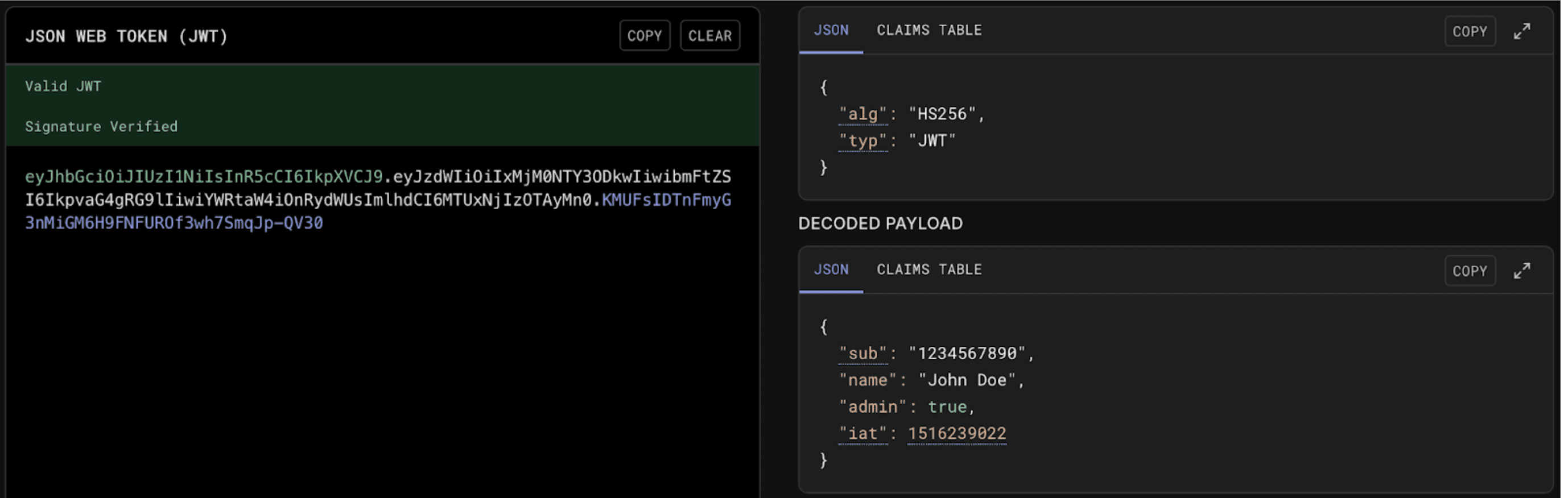

As a reminder, JSON Web Tokens, or JWTs, are widely used for authentication and authorization in web-facing applications. They frequently appear as machine-generated short-lived credentials for cloud-based applications. They show up as strings that look like this screenshot (from the online playground at jwt.io):

They’re made up of 3 base64-url-encoded sections: a header that indicates things like what cryptography is used (shown in green), a payload enumerating the claims of the token (shown in white), and a cryptographic signature (shown in blue).

There are a few standard claims, such as expiration time (exp) and not-before-time (nbf). These are very common but do not always appear. Some JWTs are issued without any expiration time or one that’s comically far in the future (like Supabase legacy API keys, which are issued with 10-year expirations).

JWTs are stateless, in contrast to traditional session tokens, making authentication and authorization possible without having to consult a database or other service. The big idea is that the permissions granted to the token get embedded within the token itself, and the whole thing is cryptographically signed to guarantee authenticity and integrity.

The statelessness of JWTs is good for scalability (at least in theory), but imposes several downsides. Most significantly, it’s infeasible to revoke a JWT, so if your JWT leaks, you're in for trouble. You can learn more about the downsides and error-prone aspects of the technology in the numerous guides written by others (1, 2, 3).

How TruffleHog detects JWTs

JWTs have distinctive syntactic structure: a couple base64-url-encoded JSON objects and a base64-url-encoded signature. Detection (prior to liveness verification) is straightforward:

Detect candidate strings that resemble JWTs using a simple regular expression.

Base64-decode and parse the candidate strings into header, payload and signature.

Filter out candidate JWTs that don’t use public-key cryptography.

A string that makes it through all these detection steps is a JWT that parses correctly and uses a public-key signing algorithm, ready to be verified for liveness.

Verifying liveness of JWTs is different from other secret types

TruffleHog’s approach to verifying the liveness of most existing secret types is the same: make a benign network request to a specific endpoint and check that the response indicates success. Its approach to liveness verification of JWTs is different. Instead of making network requests that attempt to authenticate, it (mostly) runs locally and involves two steps: verifying the cryptographic signature and validating the claims embedded in the payload.

For auth purposes, this is a delicate process where the order of steps matters. Mixing up the steps and validating the claims prior to verifying the cryptographic signature can lead to security issues (e.g., CVE-2022-23540 affecting the jsonwebtoken library and CVE-2024-54150 affecting the cjwt library).

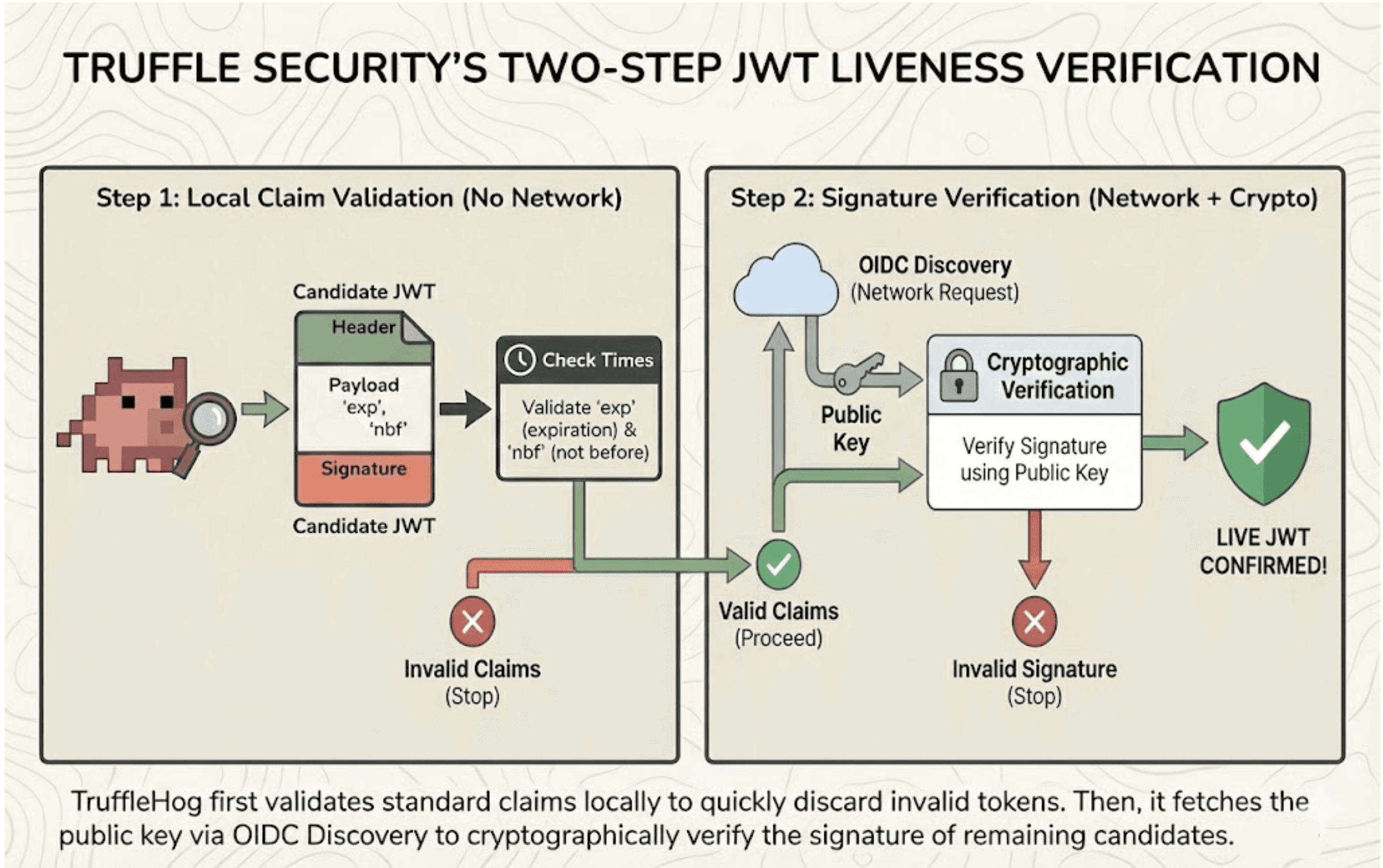

However, TruffleHog is finding exposed JWTs, not doing auth, which makes it safe to reorder these steps to minimize the amount of network requests needed for liveness verification. TruffleHog first validates the standard claims in the candidate JWT's payload, and then does signature verification.

Given a JWT, TruffleHog first checks that its expiration time is in the future and its not-before-time, if provided, is in the past. These checks are purely local and require no network access. In practice, the liveness of most detected JWTs is disproven at this step.

Once the claims of a JWT have been validated, TruffleHog then attempts to verify the signature. It uses OIDC Discovery to fetch the relevant public key, requiring two HTTP requests in the worst case. If the public key is successfully retrieved and verifies the signature, TruffleHog reports that the JWT is live.

Note that this local verification of liveness is in some sense a proxy for reality. The application using the JWT for auth might disagree with the locally-determined liveness status of a token, such as if its own token validation logic is broken or if it uses an updated configuration with different signing algorithms or key servers.

What JWTs will TruffleHog not detect today?

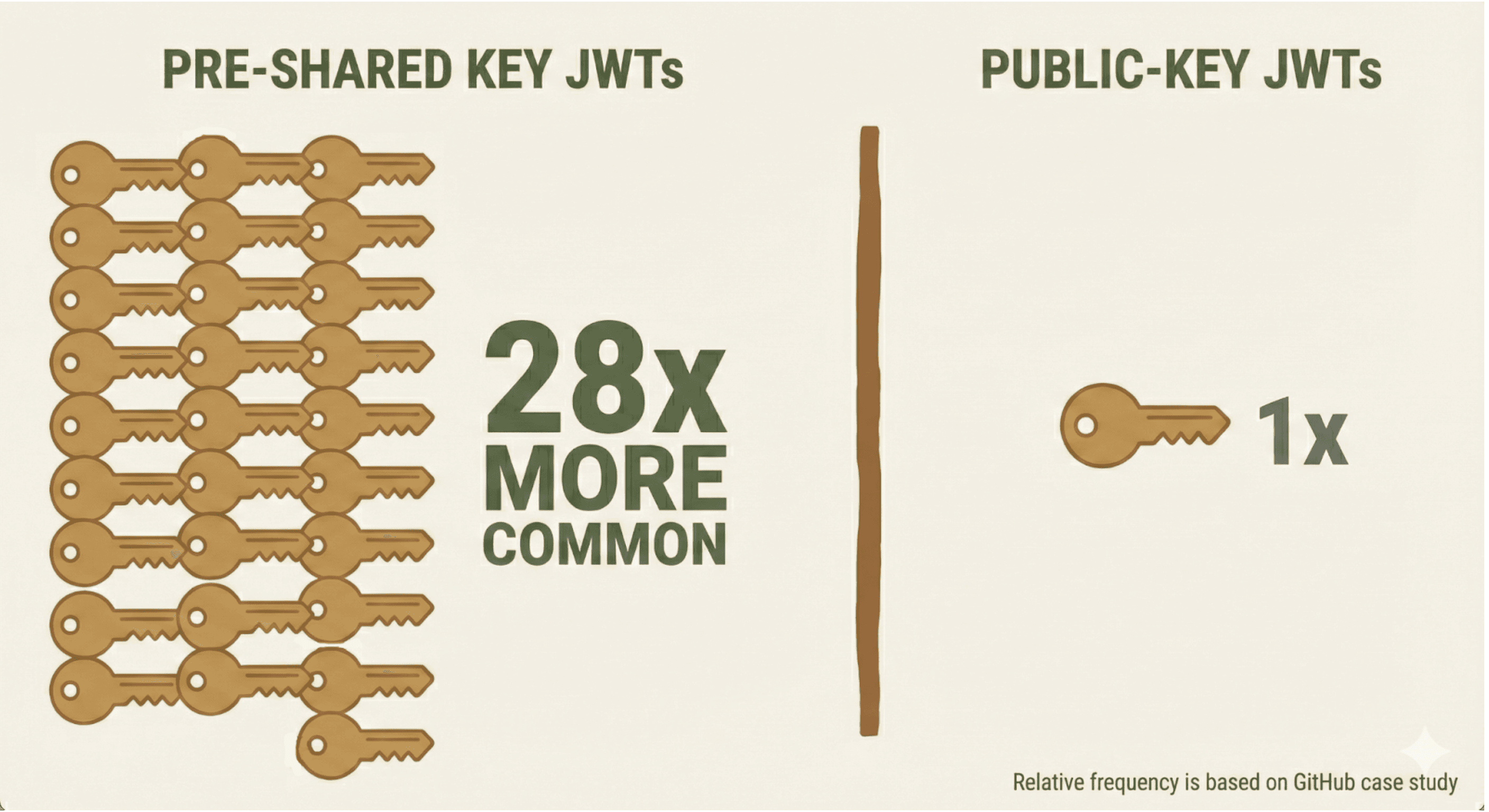

JWTs that use shared-secret cryptography

The new detector ignores JWTs signed with a shared secret (i.e., those using HMAC-based algorithms). Those JWTs are much more common than the public-key-based ones that are detected. We tested TruffleHog's new detector on several hundred gigabytes of recent content pushed to GitHub and saw shared-secret-based JWTs 28x more frequently than public-key ones. By ignoring the shared-secret-based JWTs, many potentially exposed JWTs go undetected, but we avoid reporting a glut of findings with unknown liveness status.

We are exploring options for liveness verification of shared-secret-based JWTs in TruffleHog, such as applying password cracking techniques.

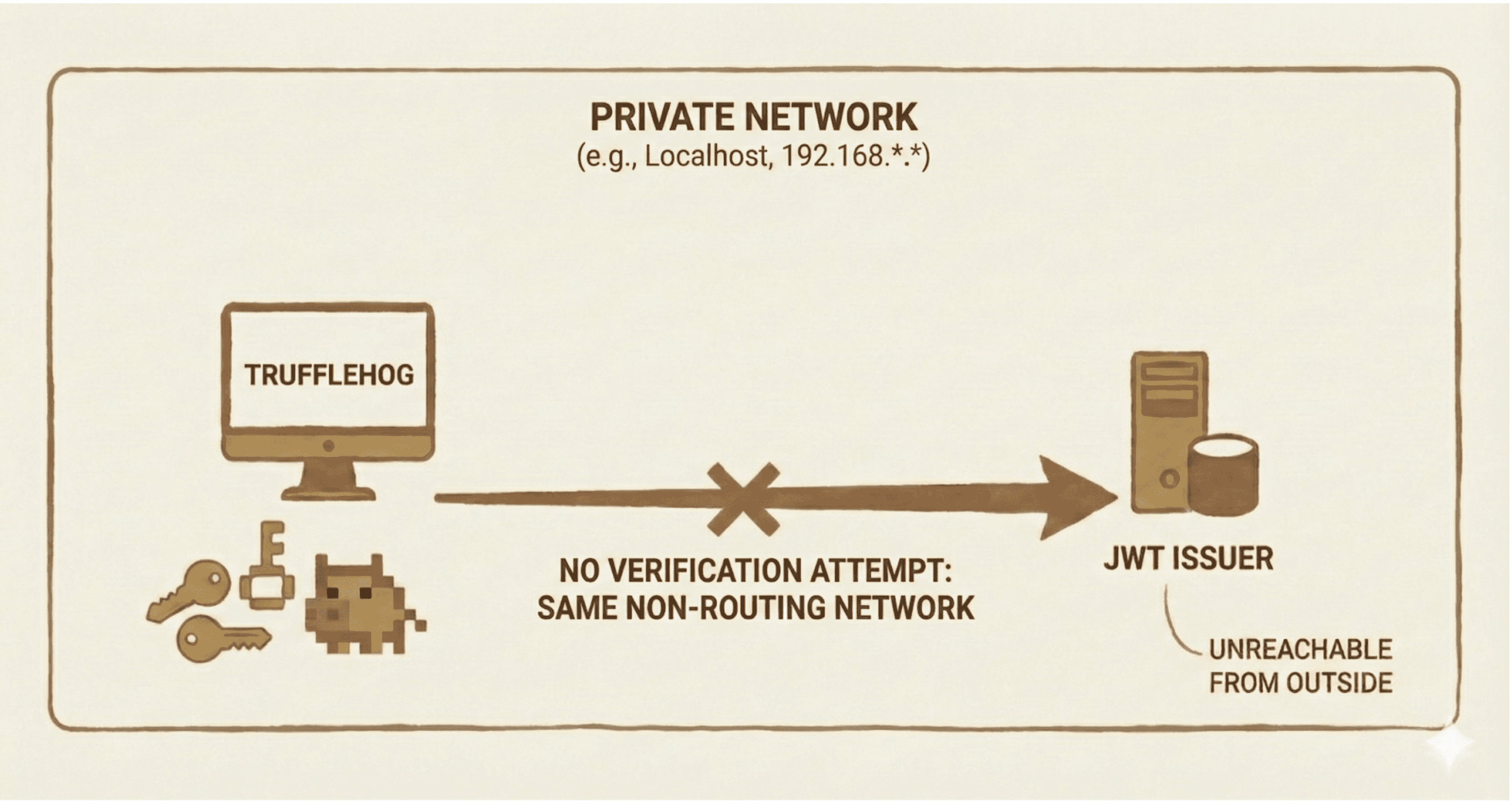

JWTs from issuers at non-routing IPs

Some JWTs are issued from localhost or other non-routing IPs (e.g., private IP ranges like 192.168.*.*). While these could in theory be verified for liveness, doing so would involve performing the OIDC Discovery protocol from the same network as the issuer. In general, TruffleHog is run from other hosts by developers, security teams, CI systems, etc. If an issuer refers to a non-routing IP, TruffleHog will not attempt to verify the token.

JWTs from issuers that don’t support OIDC Discovery

Not all JWTs that use public-key cryptography use OIDC Discovery. Some issuers share the public keys in alternate ways, like via other notable locations or embedded within the tokens themselves. TruffleHog does not support these alternates today, but they present obvious opportunities for enhancement.

It’s not always clear what applications use an exposed JWT

When a JWT is discovered, it’s not always obvious from the token itself what application or service it allows access to. Frequently there is identifying information embedded within the header or the claims, but not always, and sometimes you need to examine the surrounding context in which the JWT was found. This presents a challenge to understanding the full impact of exposure.

Remediating exposed JWTs is tricky business

Due to their stateless nature, JWTs are difficult to revoke. They usually aren’t checked against a central database that could contain revocation information; instead they are cryptographically validated based on their signature. So to revoke a JWT you are left with 3 options:

Wait for the JWT to naturally expire. This is only tenable if the JWT has a relatively short

expclaim.Swap out the signing key used by the issuer. Since signing keys are typically used to issue numerous JWTs, this will have the side-effect of invalidating other issued JWTs.

Modify the application that uses the JWTs for authentication so that it checks a revocation database. This has substantial engineering costs and eliminates the stateless property of JWTs.

If you discover an exposed JWT in your assets, you will want to find the cause of the exposure and address that through process changes or additional controls. For example, was a JWT exposed in a log file that was shared in your internal cloud storage system? Tighter default permissions for uploads and quick secrets detection could help prevent repeat incidents.

Conclusion

TruffleHog's new JWT detector has immediately proven its value by identifying hundreds of live, exposed secrets for our customers. It continues Truffle Security's approach of reporting only live, actionable findings, even though JWTs are trickier than most other secret types.